Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/helixart/public_html/blog/wp-content/plugins/wordpress-popup/inc/hustle-model.php on line 326

Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/helixart/public_html/blog/wp-content/plugins/wordpress-popup/inc/hustle-model.php on line 326

Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/helixart/public_html/blog/wp-content/plugins/wordpress-popup/inc/hustle-model.php on line 326

It had been many years since I was back, but I’ll never forget the sweet, effervescent smell of the mango trees getting ready to be fruitful. I was riding the second rickshaw, slowly enjoying the vaguely familiar sights, heavy with anticipation. My adventurous stares were met with confused, scrutinizing ones from the average passerby. Of course, I understood why: I’m an alien who just arrived– sporting a cap, a stud in one ear, necklace, aviators and earpods, Thule backpack on one side, Lowepro camera bag on the other, and a black hard-case suitcase in between my legs. Perhaps the strangest thing on my face was a smile. Yes, I completely understood.

It was March 26, 2013, and I was in Chapai Nawabganj, a city where I spent a significant portion of my childhood running through her bazaars or staring at her meandering river, the Mahananda.

Ahead of me in the first rickshaw was my uncle: Chachu (চাচ্চু) — a familial Bengali word specifying my father’s younger brother. I was certain that he could sense my eyes wandering as we got off the bus earlier. He knew it was half nostalgia and half bewilderment. You see, too much had changed for my memories to pretend like long-lost friends at a surprise party. I asked him from a distance if we’re going straight to the house; he shouts, “no, not right away, we have to stop by the court[house].”

As I followed Chachu towards the front lawn of an old building, I noticed what seemed to be a late-morning forum — an assembly of old wise men, sitting on old faded benches, passionately discussing the old doctrines of law while deciding the fates of others’. I was reaching for my wallet to pay the rickshaw fare when Chachu’s fingers commanded: “your money’s no good here.” Come to think of it, we’re big on hand-signals in my family; perhaps it’s a cultural thing, I’m not sure. However, what I’m sure of is that he’s a family member belonging to the previous generation who’s sixteen-years older than me. So I smiled and put my wallet away.

There was, however, another signal from him that made me pause.

This was more of a loaded question rather than an authoritative gesture: he touched his left earlobe and asked me with a smirk, “by the way, is that real or a clip-on?” I realized it was a subtle reminder that maybe, it wouldn’t be appropriate to draw attention to a sparkling stud where I’m headed. I thought it was nicely done, he’s a lawyer after all. Normally I wouldn’t entertain an idea like that cause it would fill me with indignation, but he had a point. I paused for a moment, took it off, and showed him that indeed, there was a hole in my earlobe. We both laughed.

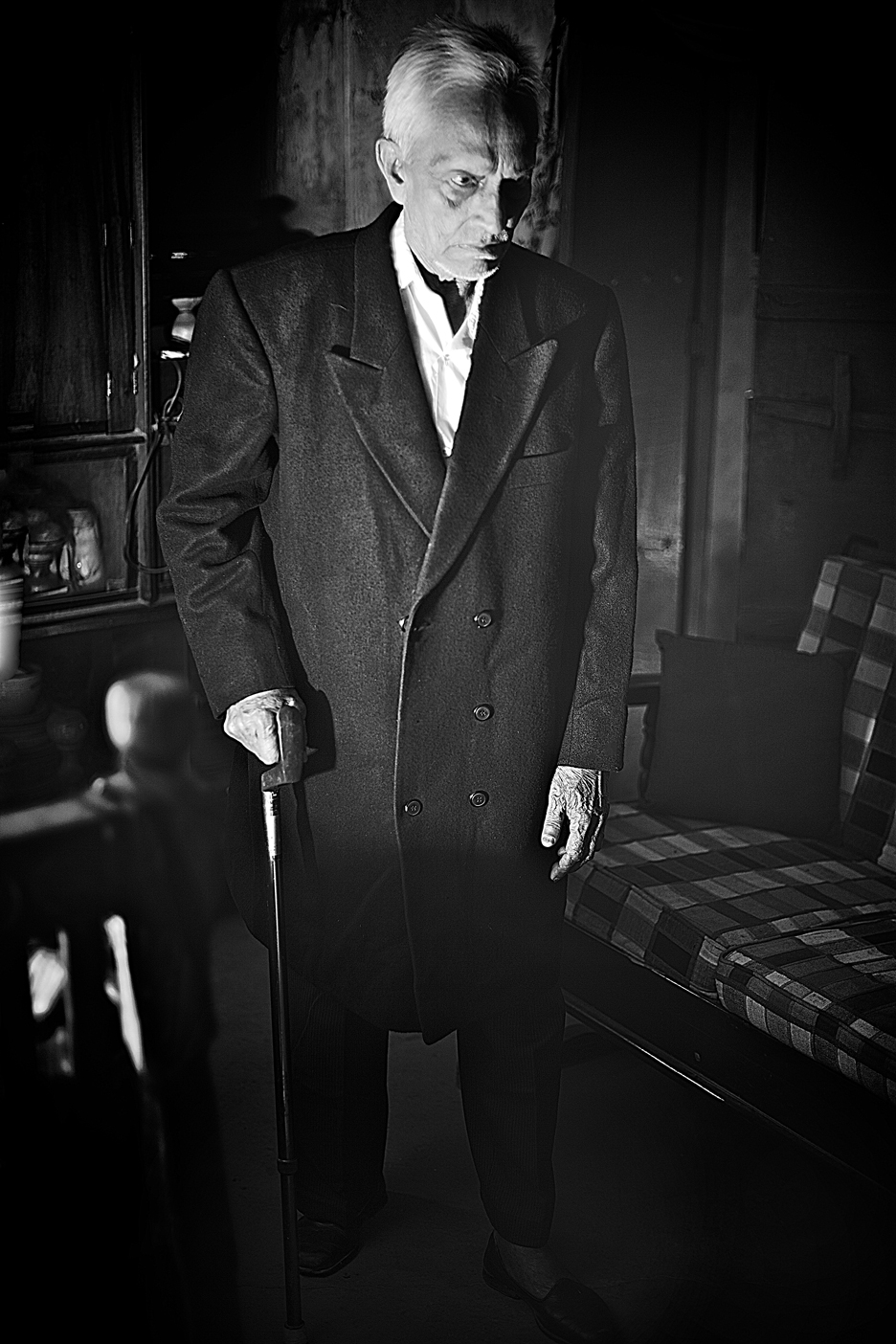

As we got closer to the gathering, I could hear a voice — dominant, full of dissertation and instruction, gargling with 89 years of wisdom. Sitting there was what seemed like Don Vito Corleone of the law himself, an intimidating giant with chapters of wrinkles and milestones of victories. His face scowling, he appeared resolute and fearless, surrounded by his colleagues and apprentices. I could hear him counseling them to look up excerpts from this book or case numbers from that book, all from memory.

Then he turned his head and saw me, his body language changing completely.

His name was Abu Sayed Muhammad Ehtisham-ul-Mulk Alhajj Tashem Mian Advocate and he was my Dadu (দাদু), my paternal grandfather.

After a salaam and a hug, I sat next to him as he began acquainting me with his audience: “This is my grandson… second eldest’s son. He came to visit me from America.” They could sense the pride in his voice. One colleague looks at me and says,

“Your Dadu is one of the most senior and revered lawyers in our whole district.” Another apprentice tells me,

“Your Dadu is like a father to me. His guidance is what made me successful today.” Then he shouts over to a boy to bring some tea for the table.

I was fascinated. It was like watching a see-saw: up, he was introducing me, and down, they were telling me about his grandeur. I looked over at my grandfather, who was nonchalantly smiling, one hand on top of his cane, occasionally spitting out the betel nuts from the paan he was chewing. He knew this chivalrous dance.

It’s rare in modern times to witness this degree of homage being paid; it’s old-fashioned. I realized then that it’s his 62 years of dedication and contribution to his profession that granted him such level of authority and reverence. That’s six decades of being a lawyer! I can appreciate that.

While I spent the rest of the day catching up with him and visiting my extended family, who were scattered across the city, an idea popped up. Since I had my 5D Mark II and luckily a Sennheiser lavalier with me, I thought why not do a photoshoot of Dadu followed by a casual interview about his life’s journeys. Wouldn’t it be neat to record nearly a century of memories or receive some words of wisdom from someone who’s been through World War II, seen the division of the Indian sub-continent, partaken in Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971? I discussed my plans with him and asked him if he had the energy to go through something like this. I could sense that he was puzzled, not entirely sure what he was signing up for, but he was definitely on board.

The Photoshoot

Dadu’s House | Photo: Hamidul Haque

diffuser/reflector, so sometimes, I’d have to hang a white bedsheet to soften the light. When in Rome, right? I also made sure he had plenty of water and rest between the shots or wardrobe changes.

He got a kick out of watching me bootstrap and run around. At one point he was so zoned into the shoot that he would come up with a pose and tell me, “Quickly, take this shot, I don’t know how long I can stay like this!” I would immediately and take four or five snaps. This was one of those moments.

We took a lunch break which gave him ample time to rest and to prepare for our next activity: the interview. I also couldn’t wait to see the images! As I was impatiently transferring the raw pictures to my MacBook Pro, he looked over at my aunt — who joined us for lunch — and said: “I have no idea what just happened, only he knows what he’s doing!” We were laughing together at his befuddlement, and then I turned my laptop around to show him the first (black & white) picture in this article. He stares at the screen, his right hand approaching his mouth pauses in midair — cupped fingers filled with rice, lentils, and chicken — he turns his head towards me, then towards my aunt, eyes glistening, and looks at me once more to give me an accolade of smiles. I said, “Dadu, that’s what we call the money-shot.”

The Interview

We started the filming soon after. I had countless questions to which he had a deluge of answers. From the meaning behind his long Arabic name — conceived by my great-grandfather in pre-1947 Hyderabad — to his vast popularity as a footballer (soccer player) to his desires to be a history professor (and not a lawyer) kept pouring out like a flood. Honestly, it felt like a therapy session, and he wasn’t the only person who was benefitting. I can’t emphasize enough how much I didn’t know about him. The interview ended after an hour and half of reminiscing his life, filled with some very personal tales. I gave him a hug, and he sobbed in my arms for the next few minutes.

Then I received my last hand-signal of the trip, and he was famous for this: it was two to three quick elastic snaps of his right wrist indicating “now go, I’m through with you for today.”

That evening, I showed Dadu the full, edited interview. He was not only overcome with joy, but he also asked me for a favor. He requested that after he passes on, he wanted me to publish a portion of the interview; which part was up to me. During the filming, one of the questions I asked him was, “If you had any advice to pass down to our generation, what would it be?” He paused for a moment and replied with the following:

I think out of all the things he told me that day, this advice resonated with me the most. Currently, in a world that is suffering from hatred, violence, indifference, we need to remember more than ever to be united and “proceed forward with respect towards each other.” It was the perfect advice, and I’ll never forget it.

Rest in peace Dadu.

You will always be respected and loved.

DISCUSSION